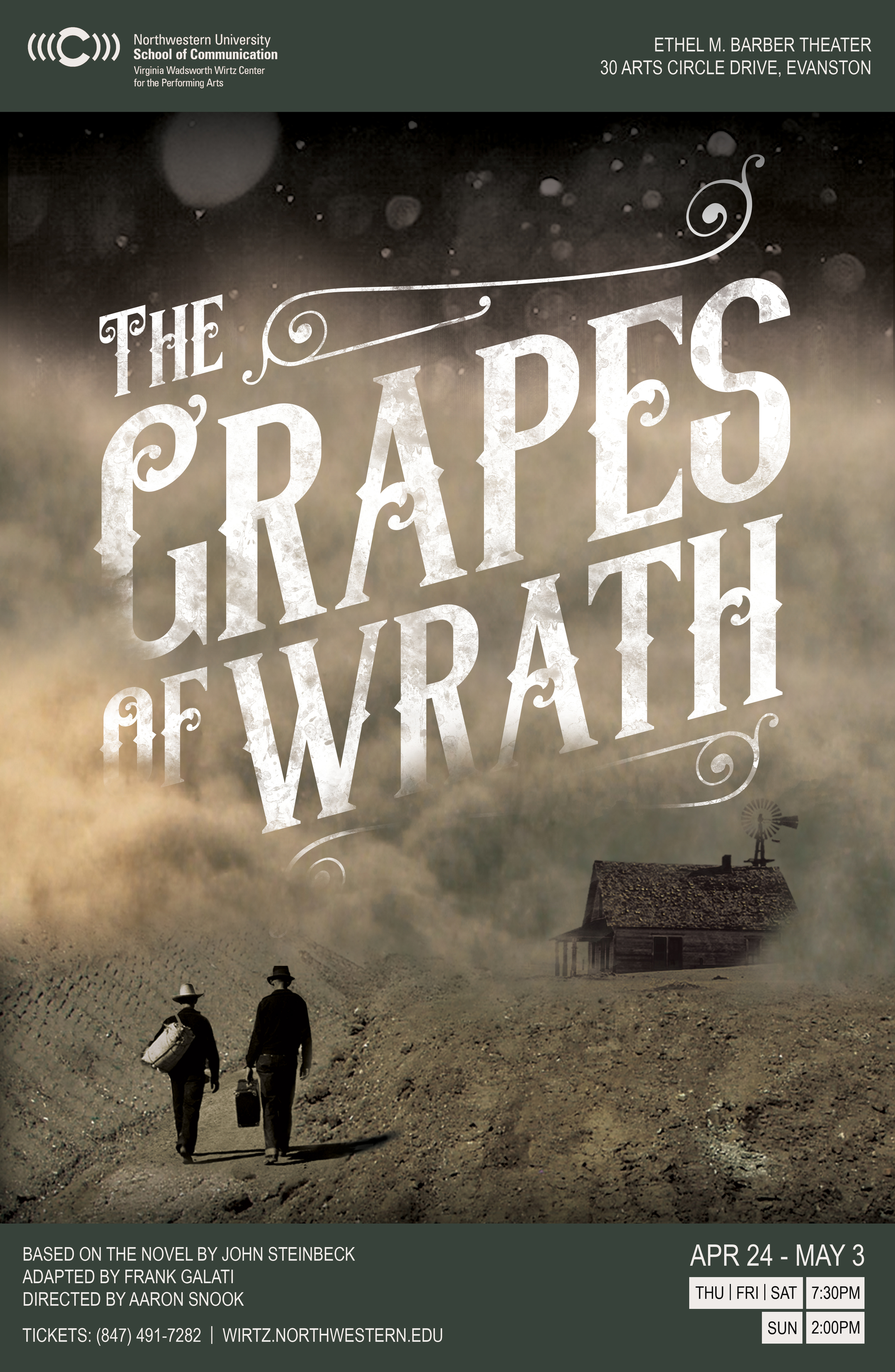

Based on the novel by John Steinbeck

Adapted by Frank Galati

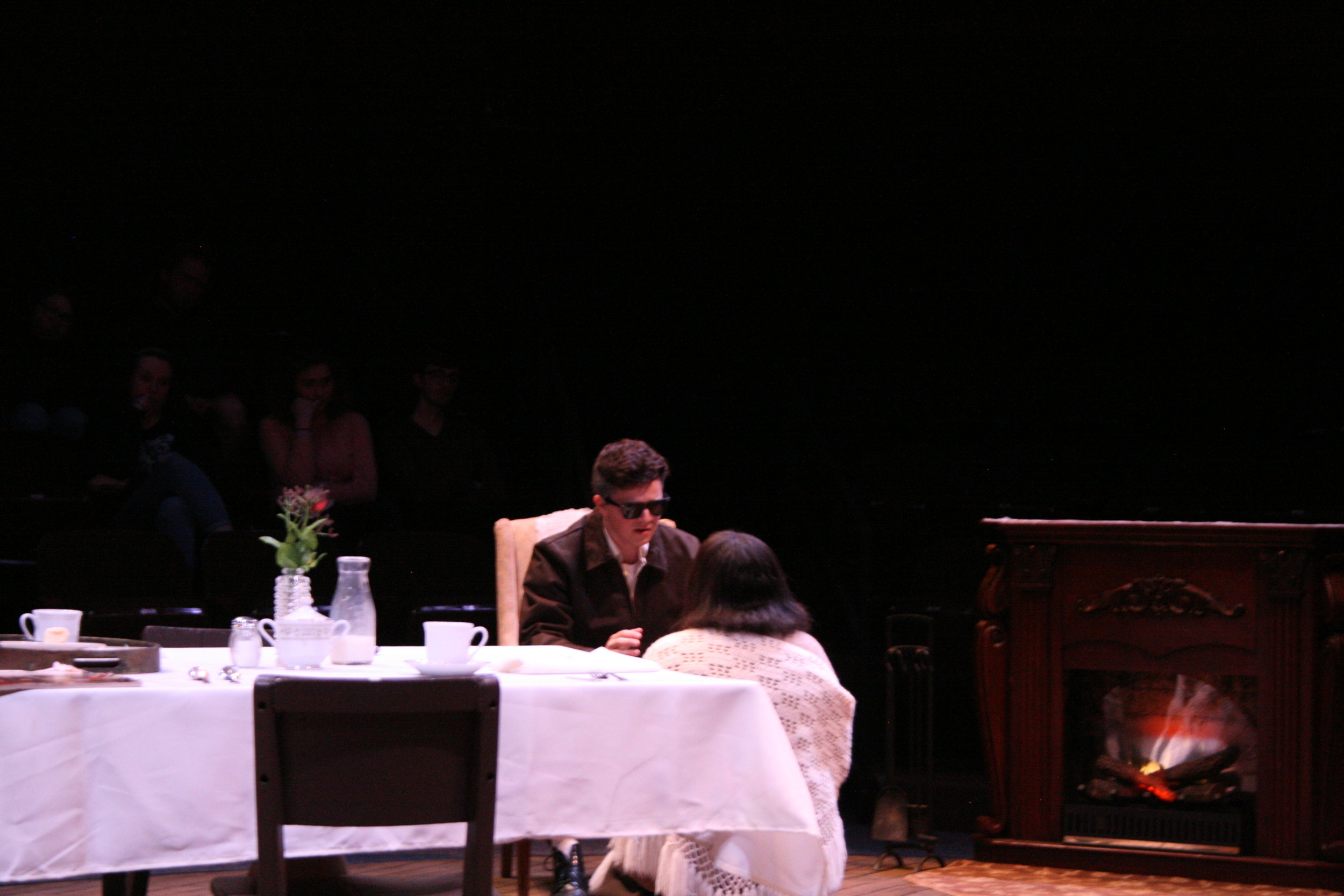

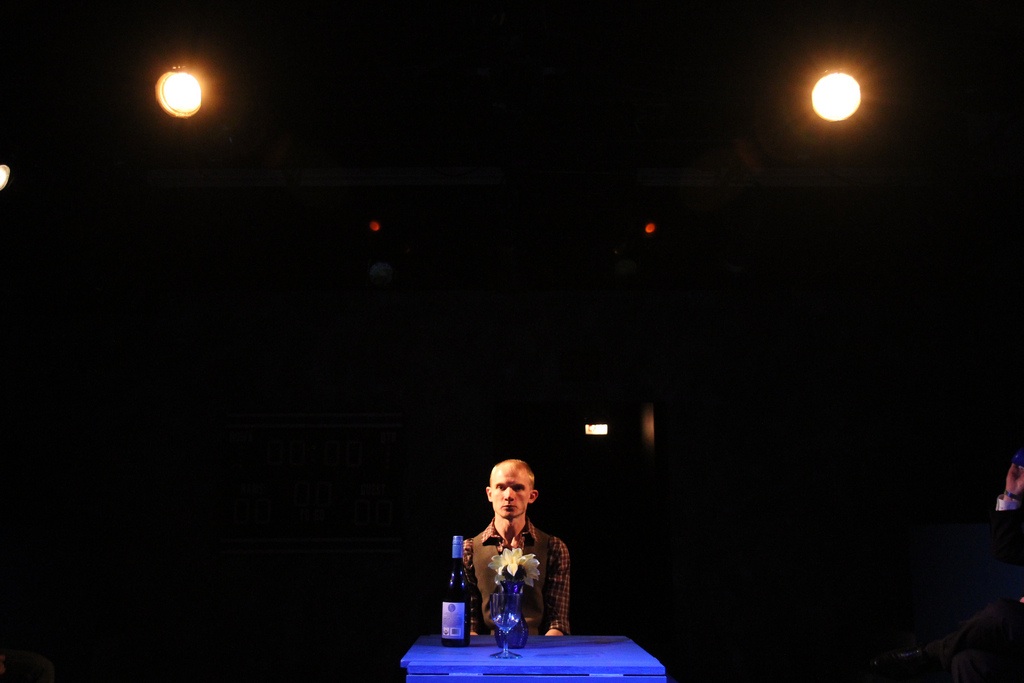

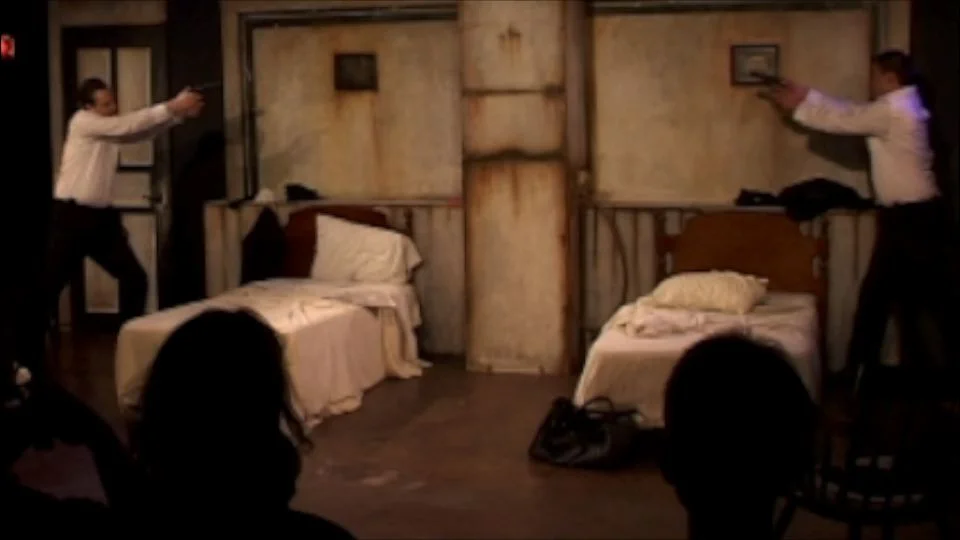

Performed at the Ethel Barber Theatre in 2015. Produced by Northwestern University

Photos by Johnny Knight Photography

Scenic Design by Arnel Sancianco

Costume Design by Caitlin DesSoye

Lighting Design by Sean Mallary

First Day Address

When John Steinbeck was writing the book that inspired this play, he wrote down in his journal that it had a chance of becoming a “truly American book.” I tend to agree.

Used to be that I wouldn’t know what that meant. Used to be I didn’t have any sense of an American identity, let along my own American identity. I was sick of the politics on both sides, I felt like our love of the almighty buck taking over and patriotism had turned into flags and catchphrases. I wasn’t proud to be an American. It made me cynical. I felt homeless.

Then four summers back, my wife and I quit our jobs and took to the road with our dog in the spirit of another Steinbeck book--Travels with Charlie. We spent three months traveling the west, and staying mostly in the campgrounds of our country. And the community that we found in these places was inspiring. Folks coming from all over, setting up for the night or more, all in common communion with the land and all looking out for each other. In a vulnerable and seemingly dangerous environment--no doors and no locks--I actually felt safer than I do in my own home. It was July 4th in the Grand Canyon when I began to redefine what America means to me. I’ll let Jim Casy, say it cause he said it best:

I got thinkin’ how there was the moon an’ the stars an’ the hills, an’ there was me lookin’ at ‘em, an’ we wasn’t separate no more. We was one thing. An’ that one thing was holy…I got thinkin’ how we was holy when we was one thing, an’ mankin’ was holy when it was one thing. An’ it on’y got unholy when one mis’able little fella got the bit in his teeth an’ run off his own way, kickin’ and draggin’ and fightin’. Fella like that bust the holiness. But when they’re all workin’ together--kind of harnessed to the whole shebang--that’s right, that’s holy.

That’s the American spirit that felt in the campgrounds of this country, that’s the American spirit I feel in this story.

The Dust Bowl was a ten-year plague of biblical proportions that landed right on the heels of the Great Depression. It just doesn’t get much worse than that in our history. And yet here is the story of the Joad family, who get tried, picked apart, thrown down, beaten and ravaged. And yet they move forward together. You all have read Steinbeck’s Harvest Diaries that I passed along. The lives of these folk, the living conditions, the starved children and utter hopelessness. This is the Joad’s reality. And yet, when their help is asked for, whether it’s Jim Casy in the beginning or the little boy in the barn at the end, they do so without blinking. They do so because they know only together will they make it. Yet, I keep asking myself, how does the spirit endure? Together, yes, but how?

I believe that there are two things in particular that can buoy the human spirit on times of desperation. The first is humor. We can’t get along without it and neither can the Joads. In fact, the worse the road gets, the more we need it. Believe it or not, this book and this play are funny. When I first read both, I can tell you that is not the impression that I was left with. Then I was lucky enough to sit down with Frank Galati and he imparted to me the truth of it. The preacher and his pecker. Granma and Grampa. The tomcatting of Al. On down the line. I just drove from Oregon and listened to the novel along the way. There were parts where I was actually laughing out loud. Without those joyful releases, I’m not sure I could make it through this story. Without these joyful releases, I don’t think the Joads could make it through their journey. It is a vital part of Steinbeck’s storytelling and it will be a vital part of ours.

In a section describing the roadside camps, Steinbeck lays out the other crucial element:

And perhaps a man brought out his guitar to the front of his tent. And he sat on a box to play, and everyone in the camp moved slowly in toward him, drawn in toward him. Many men can chord a guitar, but perhaps this man was a picker. There you have something -- the deep chords beating, beating, while the melody runs on the strings like little footsteps. Heavy hard fingers marching on the frets. The man played and the people moved slowly in on him until the circle was closed and tight, and then he sang “Ten-Cent Cotton and Forty-Cent Meal.” And the circle sang softly with him. And he sang “Why Do You Cut Your Hair, Girls?” And the circle sang. He wailed the song, “I’m Leaving Old Texas…

And now the group was welded to one thing, one unit, so that in the dark the eyes of the people were inward, and their minds played in other times, and their sadness was like rest, like sleep.

Their sadness was like rest, like sleep. Frank Galati clearly heard this and inserted live music throughout his adaptation. With his permission, I’ve tinkered with the idea and called upon one of the great Dust Bowl storytellers, Woody Guthrie, to aid us in this journey. Our musicians will be channeling him

Now, one last quote from Steinbeck (for now):

And it came about in the camps along the roads, on the ditch banks beside the streams, under the sycamores, that the storyteller grew into being so that the people gathered in the low firelight to hear the gifted ones. And they listened while the tales were told, and their participation made the stories great.

We will all come together and our stage will become one great campfire, with our audience gathered round. We will tell the story of the American spirit. We will tell it with gut wrenching honesty, humor and with music. And we will remind them (and us) that only together are we holy. No matter the odds, the strife or the loss, if we stick together as one, we’ve got a chance. That is the American spirit that I believe in and that is why I want to tell this story.

A